A View to a Kill

Essay by Professsor Frank Uekötter

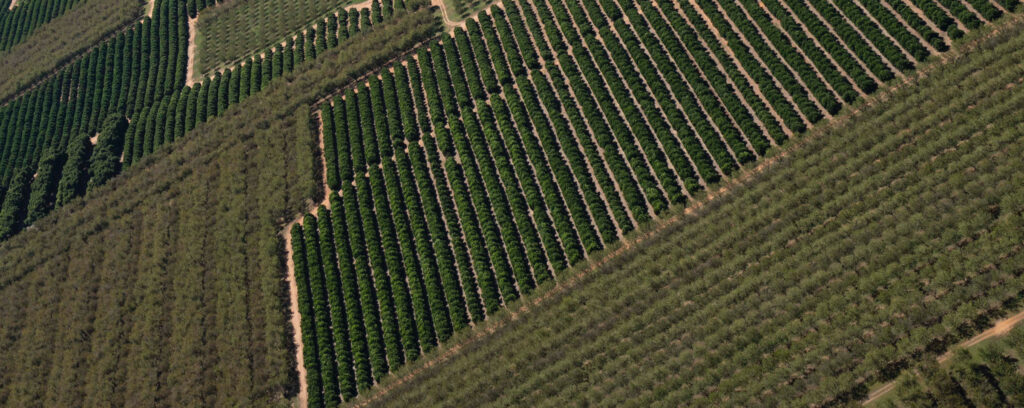

Almond orchards near Mildura. PHOTO: J Philip 2023

Article first printed in the exhibition catalogue: J Philip (October 2025) Museum of Monoculture 24 Screen Prints ISBN: 978-1-7643046-0-3

Frank Uekötter is the principal investigator of the ERC-funded project “The Making of Monoculture: A Global History” (MaMoGH). He is professor for environmental history and the history of technology at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, since 2023. He previously taught at the University of Birmingham in England from 2013 to 2023, and he launched the MaMoGH project in Birmingham in 2021.

Monoculture is not a visual story, and it is not meant to be. Monocultures are supposed to deliver food, and do so in quantities that feed a global population of more than eight billion. Every agriculturalist can tell the story of the modern cornucopia: advances in science and technology allow a dwindling group of farmers to produce more food than ever. They are less eager to talk about the toll for people and places, and they rarely come acknowledge the gaping intellectual hole at the heart of monoculture. When it comes to modern farming, we are stuck with a project that we struggle to explain, let alone justify, in clear conceptual terms.

There is a pervasive speechlessness at the heart of monoculture, which may account for the remarkable lack of artistic visualization. How can we have pictures when we do not even have words.

The drift towards monoculture is a truly global trend. Wherever farmers have entered the orbit of supercharged global capitalism, they have gravitated towards a reliance on one single commodity: in the industrialized North and the Global South, in fields, groves and barns, in bulk production and precious spices. Given this pervasive trend, one would expect that there was – and is – a robust case for monoculture, but there is none. We have plenty of conceptual and empirical evidence for biological diversity and nothing of that kind for the opposite: monoculture may well be the greatest project of global modernity that we have embarked upon without a decent paradigm. There is a pervasive speechlessness at the heart of monoculture, which may account for the remarkable lack of artistic visualization. How can we have pictures when we do not even have words?

Almond orchard on the Darling Baarka River Australia. PHOTO: J Philip 2023

Order in the Land

We have large fields with orderly rows of trees and plants, spaced for the large machines that rule in today’s agriculture. Planting, spraying, harvesting –commodity chains are mechanized to an extent nowadays that many farm products remain untouched by human hands until they are consumed. There are precise numbers for the space that machines require, just as there are numbers for the perfect speed, the dose of chemicals, the depth of tillage and so forth. Quantification is the preferred language of the world of monoculture, and it is about more than technical needs. Numbers carry an aura of objectivity and precision, they invite comparisons and call for optimization, and they suggest to the mathematically inclined that there was order in the land.

A semblance of order was much desired in the modern food business. In the world of monoculture, the daily bread was struggling with all sorts of crises. A lot could go wrong on long commodity chains that spanned the planet. Consumers changed their tastes and preferences, and expanding supplies often led to overproduction and the collapse of prices. Workers could revolt or run away. Machines could break down for lack of energy or repairs. And then there was the specter of biological threats. Large stands of identical plants are the perfect breeding ground for pests and pathogens, and every monoculture faced a multitude of challenges from Mother Nature, each of which could literally eat up the biological essence of a farming system. Producers spent a lot of money on research and technology to keep these problems at bay, but even the most powerful companies faced limits when biological challenges endured. The infamous United Fruit Company spent some US$ 140 million between 1946 and 1956 to contain a devastating fungus that threatened their traditional Gros Michel banana variety, but it failed to deliver a satisfactory response. United Fruit only survived because it switched to the disease-resistant Cavendish banana, and because it had a powerful marketing apparatus that convinced consumers that the new variety, different in taste and outlook, was suddenly a real banana.[1]

Frank Uekötter on a visit to a banana plantation on Teneriffa. PHOTO: F Uekötter 2025

The neat rows in fields and groves facilitate spraying against the biological troubles of the day, and sometimes they are also prevention strategies in their own right. Californian citrus farmers trim their trees into cubicle-sized units because it increases ventilation, which curbs the growth of fungi in brushwork. And then there are the ethnic and political cleavages that call for perennial watchfulness. Many monocultures hinged on cheap non-white labor, but their recruitment triggered white anxieties, particularly when political power was not in the hands of white men. Gregg Mitman has argued for Liberia that the strict geometric patterns in Firestone’s rubber plantations were a tool to placate the nerves of embattled ex-pats: “Order helped to rein in fears of chaos, confusion, and labor unrest that lived just beneath the surface of the idyllic world that Firestone sought to create and project for its white foreign staff.”[2]

Mildura, Australia PHOTO: J Philip 2023

Battlefield

Spraying was not the only option when biology refused to go along with the wishes of the men of monoculture. In 1932, a response of choice was the seventh heavy battery of the Royal Australian Artillery, whose machine guns were supposed to eliminate the emu herds that damaged wheat fields in Western Australia.[3] The “Emu War” had a clear winner – few birds were hit, and quite a few emus survived catching a bullet –, but there was more to the campaign than a military folly. The fields and groves of monoculture were battlefields of sorts, and the struggle to keep production alive was remarkably similar in tools and mindsets to modern warfare. In both cases, the key challenge was operating complex technological systems in a hostile environment.

The difference was that we have plenty of pictures for modern warfare but few for the battle against biological threats. A crop duster plays a side role in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, but it targets Cary Grant rather than pests or pathogens, and it was hard to give a heroic spin to the daily battle out in the land. Killing pesky insects was rarely seen as more than an agronomic necessity, and few people had an idea of the complexity of the endeavor. Using the right chemical at the right time in the right dose was a task for professionals, but there were no popular narratives for their job. And who had a proper understanding of how deep plowing, a common way of curbing weed problems in the age of high-powered tractors, put soil structures and humus layers at risk?

… monoculture leaves a void in our cultural imagination. It is about thoughtlessness, about convenience …

The troubles of monoculture encouraged a take-no-prisoner’s attitude. Producers sought responses to the many crises that surrounded them, and in making choices, they rarely thought about more than costs and benefits. Side effects were for others to worry about. When Queensland farmers found that their sugarcane fields turned acidic, they sought lime from the cheapest place that could deliver, which happened to be the Great Barrier Reef. Coral mining began in at least twelve areas around 1900 and continued over four decades.[4] The battlefields of monoculture extended far beyond the places of production.

Beyond Words

The Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh has drawn attention to the notable cultural inertia of the history of petroleum: it “produced scarcely a single work of note.” In his judgment, the toll of our infatuation with fossil energy was beyond words: “The history of oil is a matter of embarrassment verging on the unspeakable, the pornographic.”[5] One might say the same about modern agriculture if it were not for all the happy pictures that we have in our heads: bucolic landscapes, smiling farmers, delicious-looking food. Many of these pictures were the product of carefully crafted propaganda from agrobusiness. Others are mere leftovers from the bygone age of premodern farming, when most people lived in the countryside rather than cities. We have plenty of stories when it comes to our food, but they have as much to do with the reality of farming as James Bond with the daily routine of the British civil service.

Many studies have shown the social, economic, political and ecological costs of narrow agricultural specialization, and yet monoculture leaves a void in our cultural imagination. It is about thoughtlessness, about convenience, about the cultural hegemony of a carefree mass consumption paradigm that refuses to die. But maybe there is something else: a stubborn inability of our culture to connect the dots. Maybe it would be different if we had something visual that allowed us to recognize our long and fateful love affair with monoculture, and our own roles in that ongoing story. The field is wide open for artists with an independent mind, a concern for real-world issues, and the creativity to envision the invisible. And what would better show the power of the arts than guiding us towards a path that finally brings us to see the full picture!

[1] Stacy May, Galo Plaza, The United Fruit Company in Latin America (Washington DC: National Planning Association, 1958), p. 155; John Soluri, Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption, and Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), pp. 180-83.

[2] Gregg Mitman, Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia (New York: The New Press, 2021), p. 182.

[3] Murray Johnson, “‘Feathered Foes’: Soldier Settlers and Western Australia’s ‘Emu War’ of 1932,” Journal of Australian Studies 30 (2006), pp. 147-157.

[4] Cf. Ben Daley, Peter Griggs, “Mining the Reefs and Cays: Coral, Guano and Rock Phosphate Extraction in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, 1844-1940,” Environment and History 12 (2006), pp. 395-433.

[5] Amitav Ghosh, “Petrofiction: The Oil Encounter and the Novel,” Imre Szemann, Dominic Boyer (eds.), Energy Humanities: An Anthology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), pp. 431-440; p. 431.